photo by Deirdre Visser

Image description: A large group of people gathered around a central smiling person, they seem to be joyous and are dancing and lifting their arms to the sky or clapping with a brick wall behind and mosaic patio. One person has a shekere rattle in their hand.

SKYWATCHERS

Towards a Slow Art of Belonging

For the last decade, Skywatchers – a program of ABD Productions – has been bringing artists into durational, collaborative relationships with residents of San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, interrogating the poverty industrial complex and positioning community voices in the civic discourse through the arts. Skywatchers is rooted in the belief that relationship is the first site of social change, that large-scale transformation begins with intimate, interpersonal interaction, and that all stakeholders are transformed in this process – artists, participants, and witnesses. Skywatchers co-create works of art rooted in resident lives and experiences; we also hold weekly rehearsals and arts-based meetings in supportive housing sites in the Tenderloin, a youth program in collaboration with Larkin Street Youth Services, and a leadership academy in collaboration with Glide Foundation, among other arts-based partnerships and projects.

The sections here are excerpted from our full program publication by the same title: SKYWATCHERS: Towards a Slow Art of Belonging, published Spring 2021.

This is the story of Skywatchers

Rooted in the Tenderloin neighborhood (TL) in San Francisco, Skywatchers is a grassroots community arts ensemble working at the intersection of the arts and the daily struggle for social justice. This is the story of our history, our values, and our practice, animated by some of the countless moments that live inside it.

In 2014, we first sat down as a staff of eight artists to write a handbook, we imagined an audience of prospective staff members. We wanted to formalize the Skywatchers methodology, articulating a practice based on 10 years of onsite experience contextualized within the histories, ideologies, and practices of artists and movement workers who inspired us as we’ve made dozens of cross disciplinary artworks in a diverse community of makers and audience members. We’ve had countless challenging conversations and just as many extraordinary creative successes.

We’re still cultivating and collaborating on the handbook, a living document that attempts to hold our stories, and share our processes and methodologies with a broader audience of community-based artists, curators and arts presenters seeking to engage diverse communities in their programming, and community members with whom artists seek to collaborate. This document is a sample, some of what has emerged from all of our experiences, and from each conversation and performance gesture.

It is our hope to transparently share our process and practice with you, contributing to a broadening discourse about the role and history of community-based art, a practice we understand to be deeply relational, durational, and dialogue-driven work that is created across many axes of difference.

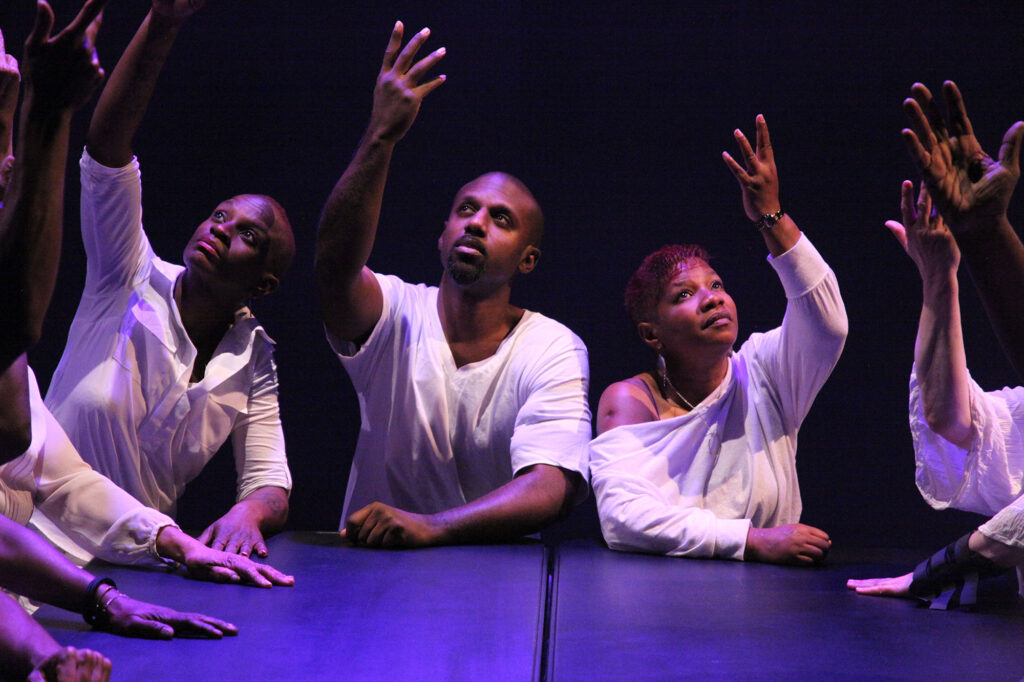

photo by Deirdre Visser

Image description: A group or eight people are seen seated around a table. Seven of them have their hands or forearms resting on or pressing into the table. All of them have one hand lifted up towards a light emanating from above. The background is black and everyone is wearing white.

“Together, Skywatchers is co-creating work that at once celebrates our shared humanity and speaks directly to the most profound ruptures of our society. We position our work strategically in the public domain and the civic discourse with a shared commitment to addressing structural inequity.

We are learning to collaborate in ways that are beautiful, rigorous, powerful, and true to community concerns and urgencies. We are learning every day.

Witnessing and creating together, we discover and invent myriad ways to embody, agitate, celebrate, and render complex stories in eloquent ways that feature the talent and creative abilities of ensemble members. The distinction between self-described artists and community participants is one that we deliberately and regularly transgress in our work, claiming our individual experiences and expertise without placing comparative values on our respective contributions.”

Our process is our product.

Anne Bluethenthal, Founder and Associate Artistic Director of ABD Productions and Skywatchers

photo by Deirdre Visser

Image description: A group of eight people, seemingly on a stage, grasp their forearms with their left hands in a lunge stance in front of white sculptures that resemble the sails of ships. Everyone is wearing white clothing and the group seems diverse in terms of age and ethnicity.

More people are writing their poetry or speaking up their mind, more people are getting involved.

They have a lot to say. I guess before they didn’t have a forum to voice themselves on.

Rita, longtime Resident Ensemble member

Who We Are

We believe that relationships are the first site of social change.

The Skywatchers Ensemble is an enduring dialogic performance-based and cross-disciplinary community arts program in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, informed by an ethos that large-scale social change begins with forging durational relationships of trust. A mixed-ability ensemble composed of professional artists and Tenderloin neighbors subject to conditions of housing insecurity and disenfranchisement, the collaborative partners together create works that amplify underrepresented stories about neighbors’ lives, histories, and urgencies, and then position these voices strategically within artistic and civic discourses.

Our Values

Collaborative

Skywatchers Artist Facilitators engage in enduring collaborative relationships with Resident Ensemble members on projects large and small, and involving a broad range of disciplines and creative practices. All are arts-based celebrations of the lives, histories, wisdom, talents, victories, challenges, and urgent concerns of Skywatchers participants.

Community-Centered

The Skywatchers process is “of, by, and for” its participants-residents of the Tenderloin and beyond. In collaboration with Skywatchers Artist Facilitators, community members become storytellers, co-creators, performers, and audience members on a creative platform of their own making.

Change-Making

We distinguished among four types of art for social change: celebratory art, art with political content, interventionist art, and community-engaged art. Recognizing that there are intersections among them and projects that integrate some or all of these practices, we nonetheless felt that it was important to articulate the characteristics that define them. We bridge community-engaged art, celebratory art, and interventionist practices in the service of social change. By building community, nurturing self-efficacy, and cultivating access to personal and creative resources, Skywatchers supports participants in becoming effective agents for change in our own lives.

Community Building

Leveraging strategic partnerships with a cohort of cross-sector stakeholders, ABD is able to effectively build local coalitions, nurture new audiences within and outside the neighborhood, and position resident artists’ work in a variety of public settings. In this way, and because all performances are free and open to all, Skywatchers reaches artists, co-creators, and audiences beyond the traditional theatre-going population.

Connective

The connectivity intrinsic to creative collaboration helps participants build trust in each other. Skywatchers is plugged in throughout the community (via our aforementioned 15 partners) so the work we do serves as connective tissue among many neighborhood groups, organizations, and initiatives.

Humanizing

The conditions of life in the Containment Zone are dehumanizing: Residents experience persistent micro- and macro aggressions that are a daily assault on one’s sense of worth and value, daily deprivation of human needs, and daily confrontation with a street-life that’s a product of oppression and perpetuated by civic neglect. All these things are dehumanizing. Through the work we’re doing, we aren’t so much humanizing, as undoing the dehumanizing effects of structural oppression, by affirming with every part of our process and product the humanity of every individual involved. Being heard and also seeing one’s own story in a broader social context creates the space for ensemble members to imagine and manifest change.

Strategic and Multi-Disciplinary

Skywatchers events range from site-specific performance installations to formal theatre-based works; from drumming circles to memorial processionals; from documentary film to dialogue as art; from public performance to intervention; and from open mics to photographic portraiture. Each work emerges from the will of the community, the resources at our disposal, and the talents and strengths of all artists involved. The form is selected to best position resident voices in arts and civic discourse.

HOW WE WORK

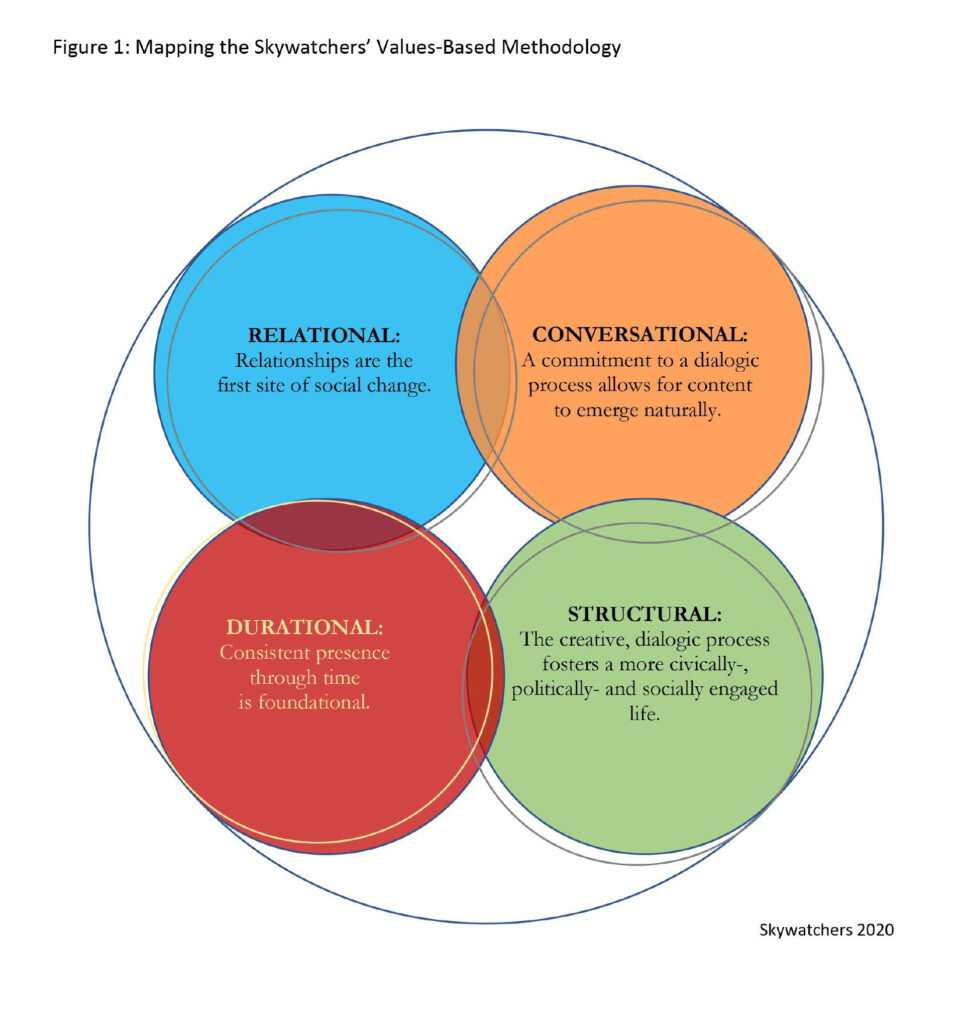

Relationship-driven and non-prescriptive, Skywatchers’ methodology focuses on collective creative process over artistic product by emphasizing four key values: Relational, Durational, Conversational, and Structural as shown in the figure above. Anchored by these values rather than an aesthetic or narrative agenda, the artistic products manifest as formal performance, arts-based organizing, or creative advocacy. The practice can be responsive to community needs while also offering long-term scaffolding for collaborations among Tenderloin residents, artists, and service providers.

Relational

Skywatchers is structured on the belief that relationships are the first site of social change. Consistent with the Social Ecological Model of public health, this asserts that larger-scale community and structural change begin with bonds formed by intimate, interpersonal exchange. It prioritizes building radically reciprocal, caring relationships of trust across differences (of race, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, dis/ability, etc.), living outside of our comfort zones, and resisting transactional interactions. It is grounds for vital, emergent, creative processes.

Durational

The second foundational element of Skywatchers’ methodology is duration, a commitment to “move at the speed of trust” (Brown, 2017). Skywatchers artists have shown up weekly at multiple program sites for nearly a decade. Their reliable presence creates structures for participants who attribute their heightened sense of belonging and decreased social isolation to Skywatchers. The other three elements – relationship building, emergent conversations, and structural change – all take time, as do iteration and evolution of the art.

Conversational

In Skywatchers, community residents drive the work; shared vision evolves collectively through conversation. Relationships of trust, built over time, grow through a spirit of curiosity and discovery that happens in ongoing dialogue. Skywatchers’ conversations are purposefully open-ended to allow for strengths, needs, priorities, ideas, and problem-solving to emerge directly from community members and result in artworks that are urgent and exciting. This does not mean that the process is unstructured; rather it is purposefully structured around dialogue that begins without knowing what the outputs or outcomes will be. Although these unknowns may be challenging for funders and partners, they are most critical.

Structural

Skywatchers’ creative process and its resulting artistic footprint appear to have engendered more civically-, politically-, and socially engaged lives. The program’s foundations – relationships of care and trust built over time, reciprocity, and a strong community of collaborators – cultivate the conditions for collective action, meaningful social change, and the possibility of influencing the world in ways residents report they had not thought possible. As individual stories are joined by a chorus of similar stories, they inevitably illuminate a shared social, cultural, and political landscape and yearning for change. The artworks situate personal narratives within the larger structural justice and equity contexts and embody, animate, and confront difficult political issues in heart-opening, humanizing forms.

Applying arts-based processes to advocacy, the program also cultivates leadership from within the community. In 2017, Skywatchers launched its Leadership and Political Education Program (L&PEP), which graduated 40 community residents (in 4 cohorts over 3 years) who have continued to engage in creative protest, community organizing and advocacy. As Skywatchers’ rootedness in Tenderloin SROs deepened, the program fostered the development of a network of neighborhood anchor organizations based on reciprocal, cross-sector, and instrumental collaborative relationships that has been working to effect policy change.

photo by Deirdre Visser

Image description: Three people are seen singing or calling out on the street. There is a central figure that holds a microphone with their hand and index finger point to the sky.

UNDERSTANDING POWER and PRIVILEGE

One of the most pernicious and complicated challenges of talking about privilege is that it’s typically invisible to those who have it, while felt deeply by those who don’t. It is a truism to say that there are pervasive structural inequities in our society based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, national origin, age, and educational attainment, among many characteristics intrinsic and extrinsic to us. Recognizing this as the ground on which we all stand, power and privilege can also be context specific, functioning on both interpersonal and structural levels. In other words, we may hold power in one arena while feeling relatively powerless in another. We invite each other to reflect on both situations, how we feel in each, and what we assume about the person or people who are at the opposite end of that spectrum in a given setting.

There is always an enormous amount we don’t know about the experience of others. Our task is to listen and be attentive to our assumptions. This is especially true when we engage with communities of which we are not a part. In Skywatchers we create spaces that encourage multi-modal and diverse expressions of creativity and intelligence, freedom from oppression and discrimination, and mutual respect. The facilitation of such a space invites staff members to reflect honestly on the power and privilege we hold in the project, and the assumptions we may carry about our collaborating partners. Our dress, behavior, education, and employment status may mean that we are treated differently than some of those around us. Conversely, where we may be taught to see scarcity, abundance also resides.

In Skywatchers, we practice entering from a place of curiosity and self-reflection, using the following as guideposts:

Listen to ourselves more clearly.

We’ve all grown up surrounded by stereotypes. We tend to be especially attuned to the assumptions that seem to reflect negatively on a group with whom we identify, and less conscious of those we hold about others. It takes ongoing and rigorous work of self-observation, humility, and openness to examine our preconceptions. Cultivating the ability to listen with an open heart-mind – with curiosity and attuned to our own reactivities – is essential.

Ask questions.

In community we encounter not only our own preconceptions about others, but others’ beliefs about each other and about who we are and where we come from. Though we may hear a statement that does not sound or feel right, asking questions is an act of generosity; saying, “This is what I heard; is that what you meant?” assumes good intentions. Genuine curiosity creates an environment where we are all learning from each other.

Speak from our own experience.

The corollary to this is that we ask others to speak from their own experience as well. While we may perceive that we share an identity with someone in the room, the ways that one facet of our identity intersects with other facets may not be the same, and therefore the impact will be different. For example, we may share another participant’s sexual orientation, but our experience of that identity is informed by our religion, family structure, class, education, ethnicity, generation, and geographic location, among other factors.

The process of inquiring into the places we do and don’t hold power and privilege is alternately challenging and humbling; in either case it’s ongoing, and it’s a process that we enter into both individually and organizationally so that we can better understand our roles and be more effective and creative collaborators.

REFLECTING on POWER and PRIVILEGE in the ARTS

Cultural theorist Grant Kester has written extensively about community-based art, critical of the tendency that community-based artists have to imagine that through the medium of art they can transcend differences between themselves and the community with whom they’re working. Widespread, too, in Kester’s analysis, is the assumption that the underserved communities that artists typically enter are not themselves politically coherent, and that art has an ameliorative effect on a broad range of social ills. This lends a paternalistic air to many projects, and underestimates or discounts the cultural integrity and power held in that community.

Artists, like galleries or theaters, are not culturally neutral; artists are themselves products of multiple social and cultural contexts. As an artist entering a community that is not your own, or as a community member collaborating with artists to share stories and envision and manifest change, this is an invitation to take a leap of faith, listen with curiosity and humility, be attentive to one’s own assumptions, and engage in a reciprocal process of learning. While we share Kester’s belief that art doesn’t ameliorate or erase differences of experience, access, history, or oppression, we do believe that the participation in collaborative creation can be personally transformative, foster community, and serve as a productive medium for dialogue across difference.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, we find ourselves situated within an arts community that self-identifies as socially engaged and progressive. It is largely thanks to the relative interest and support for work that operates at the intersection of art and social justice that the imagination of programs like Skywatchers is possible. While this feels particularly true in the Bay Area, art projects that respond to the current socio-political climate are also gaining momentum nationally and internationally. If artists and community are two points of the triangle in this practice, arts institutions serve as the third. These organizations may serve as a performance venue or sponsor, and are variously able to provide visibility, infrastructure, and institutional support. Despite the professed desire or manifest action to engage meaningfully with a diverse community, there is nonetheless often a class disparity and cultural divide between the institutions and the communities they hope to engage.

The Arts and Gentrification

In the last few decades arts funders and civic agencies have privileged capital campaigns for venue acquisition, and those same leaders and developers see the arts and culture as the avant-garde in transforming economically blighted neighborhoods. This has meant that art venues are often located in or at the edge of depressed neighborhoods, becoming – whether intentionally or not – complicit in the wave of gentrification that has displaced whole communities, and transformed inner cities across the country after preceding decades of subsidized white flight to the suburbs.

As the Skywatchers Ensemble steps across the divide and into these arts venues, the intersection of cultures affords us an opportunity to witness and reflect, on the one hand to see the fertile ground for an intersection that could be fraught with micro-aggression and unconscious bias, or on the other hand, a locus of real institutional learning and relationship-building across differences. In the latter case we have the opportunity to facilitate what many well-meaning venues speak to but often do not know how to realize: the transformation of an elite art space – to which access is literally and figuratively contested – into an inclusive, welcoming space that is embraced and enriched by its neighbors.

Cultural Norms Aren’t Neutral

On dress/tech rehearsal and performance days, we typically make a call time up to three hours before the show starts. This means the artist facilitators might arrive at the space even earlier than that to set up, prepare food, or make reminder phone calls. Community ensemble members might arrive before call time as well, coming to rest, eat, get dressed, practice lines, and catch up with one another. The downtime – moments not spent rehearsing or actively creating, but instead hanging out and eating together – is an important part of our work together. This style of pre-production convening isn’t a cultural norm in the performing art world, and at times it has felt clear that theatre staff are uncomfortable, and organizational systems have difficulty accommodating new norms.

At the Front Door: Access and Entry

Balancing security and accessibility is a dilemma faced by most venues these days and the arts community in our city is no exception. Most spaces have some form of security upon entering, whether that takes the form of keyed entry, codes, staffing, or call-in systems. They are all put in place as a barrier to entry to the neighborhood passerby. If there is a theatre employee watching the door, how do they determine who to let in? Do they know the neighbors? We have seen institutions aim for a welcoming, non-biased atmosphere of inclusion, and others build in more physical and social barriers fueled by unconscious bias and suspicion.

Accessibility also comes up in the architecture and location of an institution. Many of the Skywatchers Ensemble members use wheelchairs and walkers to move through the world, both on and offstage. This is disproportionately true in low-income communities who often face more barriers to good healthcare, live in food deserts, and have experienced higher levels of trauma. Access issues are experienced as barriers when moving across the city on public transit or entering buildings unaccustomed to supporting performers of multiple abilities.

What has served our community best has been a genuine attitude of curiosity and reciprocity of learning. This bodes well for building good community relationships. In making organizational decisions, it can be valuable to remember that the behaviors and economies that play out on the street are the result of deep and intergenerational inequities that disproportionately affect low-income communities of color.

Programming

It is not uncommon for the Skywatchers Ensemble to be invited to perform as part of regular or adjunct programming. These engagements range from fully produced performances to processionals, to song-leading, to informal performances alongside political or community events or gatherings. On one such occasion, we were situated outside of a very established theater venue, on the front steps for an afternoon performance only a couple of hours before a higher profile theatre company would be presented on the main stage. The Skywatchers ensemble members were offered tickets to the theatre performance – ironically a piece about the history of the Tenderloin – performed by another professional theater company, whose performers did not have lived experience with the production themes. The company performers and creators of that main stage production were not told about – and therefore were not in attendance for – the Skywatchers performance by neighborhood residents, and there was no encouraged or facilitated dialogue between the performers of the piece and our ensemble. The irony aside, we see this as a significant missed opportunity for the type of community dialogue that this arts venue advertises.

One ensemble member, Wanda, felt that “they looked down their noses at us,” and when asked if she stayed afterwards to watch the performance about the Tenderloin onstage said,

No, I just didn’t feel right…I mean, we’ve been performing other places on stage and we’ve gotten a lot of good praise, so what was wrong that we couldn’t be there?

Wanda Jean, Resident Ensemble

Gigi agreed, also conscious of competing with the surroundings. She prefers the theatre setting, where “it’s just us and the audience and we’re in full control.” In this situation, it “felt like we were cast-offs.” She also spoke to the power of performance created by those with life experience in the subject:

That’s the interesting thing [about Skywatchers’ work]: everyone is taking part of themselves and putting it out there… People’s individual ideas and what they wanted to say was put into this story. It’s not a regular story like a play, but individual pieces that personify different parts of the Tenderloin. And you know it’s from the heart, because these are people who’ve lived this stuff. It’s not just someone sitting there writing a bunch of stuff out who’s never lived in the TL.

Gigi, Resident Ensemble member

The Geography of Comfort

In San Francisco – like many cities – crossing a street can mean entering a new neighborhood; most of us have internal barometers of comfort and belonging that sound the alarm when the terrain has changed. While there is an understanding that established arts venues – regardless of location – offer a different and favorable kind of exposure not afforded by public spaces, informal venues in SROs, or neighborhood gathering spaces, the Skywatchers ensemble members whose words appear here generally feel most comfortable when performing in the Tenderloin.

“Some of the places that we’ve gone [to perform] I just didn’t feel comfortable,” reflects Wanda. Describing the dynamic that sometimes occurs when the audience and our ensemble are sharing a space outside of the performance, she said it feels like, “Oh, here they come.” She went on:

Listen, people can give a certain type of feeling. The way they look at you, the way they talk to you…not just arrogance. It’s like, “Oh, what are you doing here?” It’s like we’ve come from the wrong side of the tracks, if you know what I mean. I don’t like that feeling.

By contrast, Gigi remarked, “there isn’t any place I don’t feel welcomed,” but emphasized the importance of having ample time to rehearse and set up in a venue in order to maximize her comfort level when performing.

Wanda named a few Tenderloin venues that “feel like home,” and expressed appreciation for staff that,

…understands exactly what everyone else is going through. Because we’re all part of the Tenderloin so therefore we’re not, you know, wondering what’s going to happen there. Because even though they don’t live in the Tenderloin, a lot of them come down to the Tenderloin to work, and they stay informed about what’s going on in the community.

She said she likes those spaces in the Tenderloin that are more established, as opposed to the Tenderloin National Forest or an informal space inside an SRO, because it those spaces bring new audiences:

I had this lady come up to me and she said, “I remember seeing you somewhere!” I said, have you ever come and seen Skywatchers? She said, “*Gasp* THAT was you?” She invited me to come and perform with them and she said you will be paid for it. It’s more exposure, because it’s a certain type of people that come there. People that can actually…movers and shakers, basically.

Speaking about our first time having a weekend run in a Tenderloin-based theatre venue, Gigi said,

I was curious about what kind of people would be coming and all that, but we got some positive reactions and that felt good, that our work had come to fruition. That all our work paid off to achieve this thing.

Comparing these experiences with a performance in the auditorium at Kelly Cullen Community, the SRO and community space where we hold our weekly meetings, Gigi added,

The makeup of the audience is better at Kelly Cullen, because we’re telling their story. Whereas the audience at [other established venues], it’s like we’re doing a play about France or something, you know? I’ve never been to France so I’m just accepting it in that way. They’re just as appreciative, but when we’re telling their stories, they can relate easier. It’s easier to get the neighborhood to come into Kelly Cullen. I don’t think the neighborhood knows [the other venues] exists, so to speak.

Making Change

Just as it’s important for artists considering starting a community-based practice to ask questions of themselves about their values and positions regarding power and privilege, it is also important for organizations and institutions to reflect on both their intentions and ability to support the Skywatchers Ensemble or another community-based company [particularly when the invited artists come from marginalized communities or communities where cultural differences are significant]. There are also decisions big and small that venues can make that can foster a sense of welcome and enhance dialogue in which all folks at the table can learn from each other. In line with the areas of concern outlined here, we encourage organizations to think about:

Access: From public transit to the front entry to the stage, are there physical and cultural barriers to entry?

Money: Will community members be adequately paid? Are tickets accessible to a broad audience?

Benefit: How does the organization benefit from the relationship, how are they willing to be changed, and how does their presence enhance the community?

While many organizations write “community engagement” into grant proposals, the work of critical self- reflection and institutional change is an exciting but challenging road. We hope for a real desire to make the arts a space to disrupt social hierarchies and build dialogue across difference, a process that few community arts organizations actually take on. In the sometimes-uncomfortable intersections between worlds are the profound possibilities for change. The story is still being written.

Slow Art and the Politics of Care in an Outcome Market

We need art. Communities use art to reveal, interpret, and imagine the conditions of their existence. So what happens when the broad needs of community-based art meet the more narrow standards and conventions of the art market? What does this mean for those of us who infuse our process with fundamental values of care and reciprocity? With relationship building and co-creation? How do the needs of a community fare under these metrics of aesthetic worth and artistic value? What gets to be considered art and who gets to be an artist, and who do those assessments serve?

The slashing of federal, state, and city funds has pushed arts funding increasingly into market-based spheres, subject to the vocabulary of commodification, privileging product over process, audience numbers over quality of relationship building and community partnerships, spectacle over duration, and external quantitative metrics versus qualitative, participatory self-assessments. Further, metrics that demand evidence of “lives changed” or “social change achieved” in one season lay the groundwork for exploitation and opportunism, just as those that expect to see programmatic and financial growth from year to year are exhausting the arts ecosystem, leading its most valuable assets into burnout.

Artists seeking funding must annually predict and justify their own artistic production. Even before establishing community with which to develop a project, artists are expected to know what their product and those measurable outcomes will be. This is highly problematic for the community-based artist for whom being open to the emergent needs, strengths, and visions of the community with whom they’re working is essential to honest collaboration.

Instead of the implication that the savior-artist and the noble artwork might have changed the community, maybe we could instead ask how the artists themselves have been changed by the work? How their assumptions and blind spots have been revealed and challenged? What is the quality and depth of the relationship? And how has the process of collaboration shifted power and dislodged the structural inequities that largely determine our lives and the art that we make.

By making funding conditional on any particular set of outcomes and standards, funders are shaping the field and predetermining a generation of aesthetic values. Our livelihood as art laborers depends on meeting those standards, even if it means altering programs, methods, timelines, and objectives to provide the quantitative evidence of “success.”

What gets lost in this scenario? What is the cost?

In both times of trouble and harmony, we need the full range of creative production – its diverse practices and forms – and we need all the makers and creators currently working, and more.

In Skywatchers we are setting the terms for our own evaluation, assessment, and impact, towards – as our subtitle suggests – an understanding of Slow Art and the Politics of Care in an Outcome Market.

We want to expose and challenge what is being privileged by these funding models and make a case for a more expansive set of values based on equity, sustainability, deep community engagement, and disruption of entrenched structural oppression. Perhaps then we would see processes of creative production that begin to dismantle these deeply entrenched power dynamics.

There is nothing more fundamental to our humanity than imagination, and nothing more life affirming than the act of creating…This is what we do. In community. Every week.

Anne Bluethenthal, Founder and Associate Artistic Director

The creation of these processes and practices have been important for Skywatchers in our growth and development but should not be treated as a how-to manual. These are a record of previous experiences in Skywatchers and a set of observations and learning experiences that we hope can be a guide, a starting point, a launch pad. We hope that it serves to spark inquiry, discovery, and further creativity. In addition to the specific practices described here, there are indispensable and intangible qualities that are both the foundation and the connective thread of Skywatchers. These are not skill sets to be acquired, but more of a pervasive attitude to embrace. Skywatchers is rooted in respect, joy, and humility. Respect manifests as the belief that people have a right to self-efficacy, and the trust that people are intelligent, creative, and good. We enjoy the company of our collaborators and learn both with and from them. Our ability to be humble within this process and amongst our many collaborators is our very door into the work.

photo by Deirdre Visser

Image description: Three people stand side by side with their hands pressed together at the sternum. Behind them is green leafy plants and a mural of a face.

We’re grateful to have shared the Story of Skywatchers with you.

FEMME-ifesto

Please click through here to read

Skywatchers Lexicon

Skywatchers Artist-Facilitators are emerging and mid-career artists working in dialogue with Resident Ensemble members (see below.) Facilitators collaborate with residents to transform the issues raised in community workshops and dialogue into creative expression, whether movement based, visual, or spoken word. The dialogue-driven creative process allows participants to see their story transformed, perhaps expanded through connection to larger social narratives, injected with humor, paired with another related story, or otherwise re-contextualized.

Collaborating Artists offer support for the ensemble in various capacities, including offering workshops throughout the Skywatchers’ season and/or supporting productions.

Community Partners are individuals and organizations with whom we have fostered working relationships in various capacities to share resources and information; to help organize and plan actions, interventions, campaigns, or programs; and to build effective alliances for change.

Containment Zone: A containment zone is a place where a city allows activities they want to keep out of other neighborhoods. Many Tenderloin residents and advocates believe that the City treats the neighborhood as a containment zone for open air drug sales and use, prostitution, and other illegal activities. The impacts of this narrative on community health are real, including persistent traumatic stress.

Conversational/ Dialogic: Since the relationship building over time is based on ongoing conversation, we alternately refer to the work as conversational or dialogic. The art emerges from conversation.

Of, By, and For the Community: In describing the community-based performance work of his friend, Maryat Lee, actor Ossie Davis used the expression “of, by and for the community.” Richard Owen Geer elaborated on this phrase, applying the values it suggests to a field variously described as community-based art, socially engaged art, social practice, or community-engaged arts practice. Of means about the community; by indicates that it’s created, authored, or performed by the community; and for means that it’s witnessed by and benefitting the community with whom the work is created.

Resident Ensemble: Though we understand there to be only one Skywatchers Ensemble, there are moments when it’s useful to distinguish between ensemble members who live in the Tenderloin and those who are local artists, whether staff or collaborating artists, who don’t live in the neighborhood. When Skywatchers began, the term “Resident Co-Creators” was used to describe participants who were residents of the Tenderloin SROs in which we held weekly meetings. Today the Skywatchers community has grown and broadened to include members who live in SROs or supportive housing settings outside the boundaries of the neighborhood, and those within the TL who are unhoused or housing insecure. We use the term Resident Ensemble with an awareness of its limits.

Skywatchers Ensemble refers to all members of the group – staff, collaborating artists, and Resident Ensemble members – who are integral to the realization of our multidisciplinary performance-based work.

Contributors

jose e. abad, Zoe Bender, Anne Bluethenthal, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Malia Byrnes, Hope Casareno, Gabriel Christian, Rebecca Chun, Melanie DeMore, Leigh Gaymon Jones, Jubilee July, Shakiri, Dazié Grego-Sykes, Donna Rae Palmer, Yanina Rivera, Deirdre Visser, and Joel Yates.

Ensemble 2021

jose e. abad, Shavonne Allen, Calvin Barnes, Anne Bluethenthal, LaWanna Bracy, Kathy Brown, Malia Byrne, Charlos the Prince of Music, Gabriel Christian, Melanie DeMore, Kim Diamond, Wanda Jean Edwards, Gigi Goddard, Maurice Hudson, Samantha Kuykedall, Freddy Martin, Te Martin, Regi Meadows, Lotus Miller, Duane Sears, Shakiri, Cheryl Shanks, Silver Sonic, Lee Staples, Deirdre Visser, and Joel Yates.